Transform Patient Care with Cutting-Edge Ultrasound Training

Join a global community of healthcare professionals mastering Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) through expert-led, flexible training programs.

124+

Countries reached through online courses

250K

Views of online courses worldwide

150+

Residency programs trained

140+

Topics covered in online courses

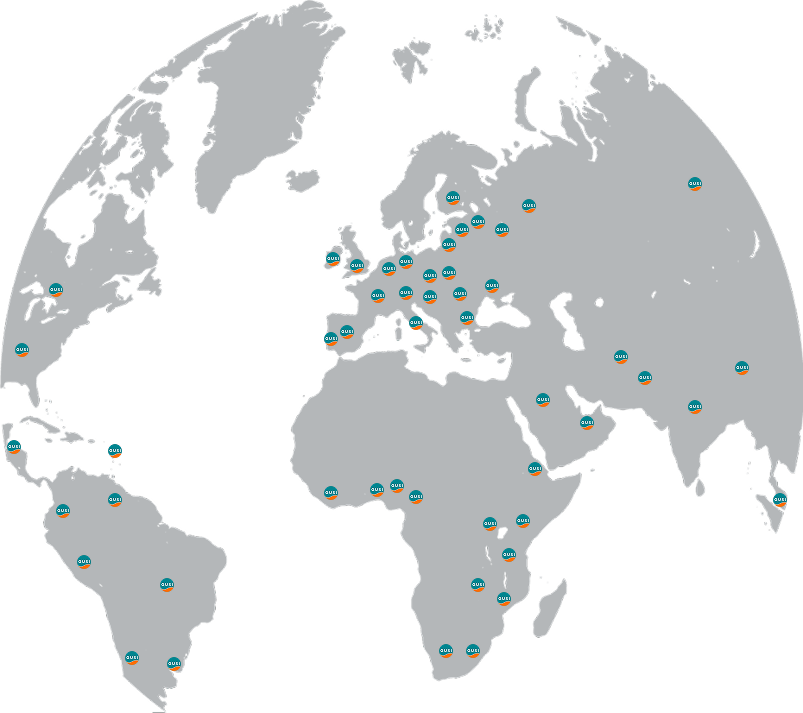

Global Ultrasound Institute proudly works with top universities, institutions and medical facilities across the United States and around the world

Why Choose Global Ultrasound Institute?

Join the world’s leading platform for Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) education. Empower your medical practice today!

Expert-Led Training

Learn from experienced physicians and ultrasound specialists guiding you every step of the way.

Flexible & Accessible Learning

Access training anytime, anywhere with our user-friendly platform and on-demand courses.

Innovative Tools

Enhance your skills with Sage AI™, our groundbreaking ultrasound training assistant.

Global Impact

Join a mission to improve healthcare outcomes worldwide, especially in underserved communities.

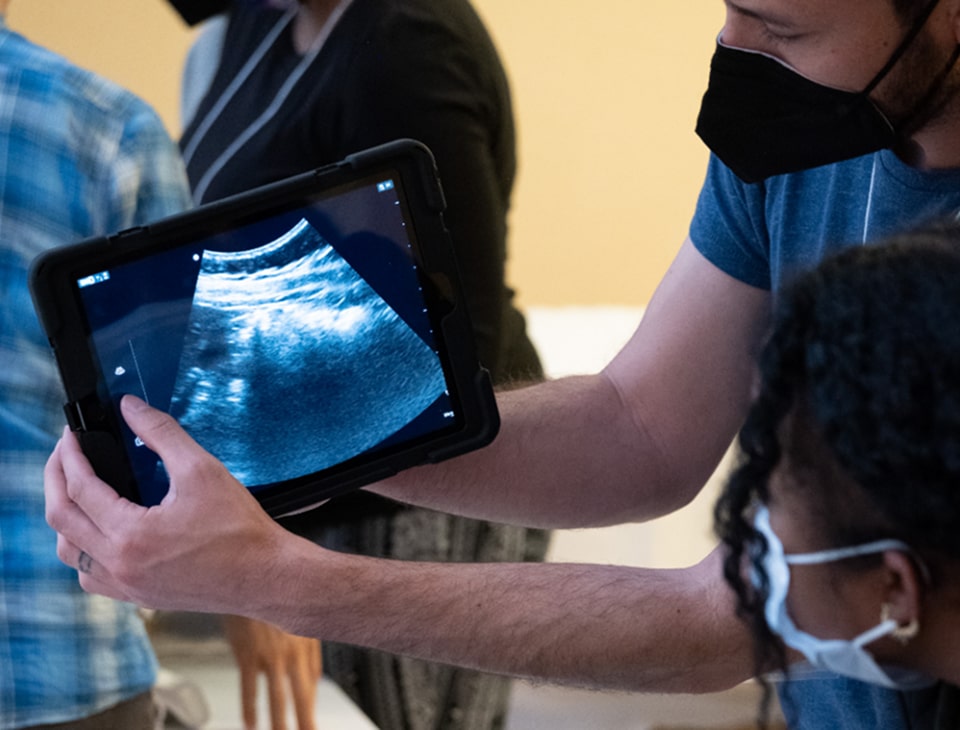

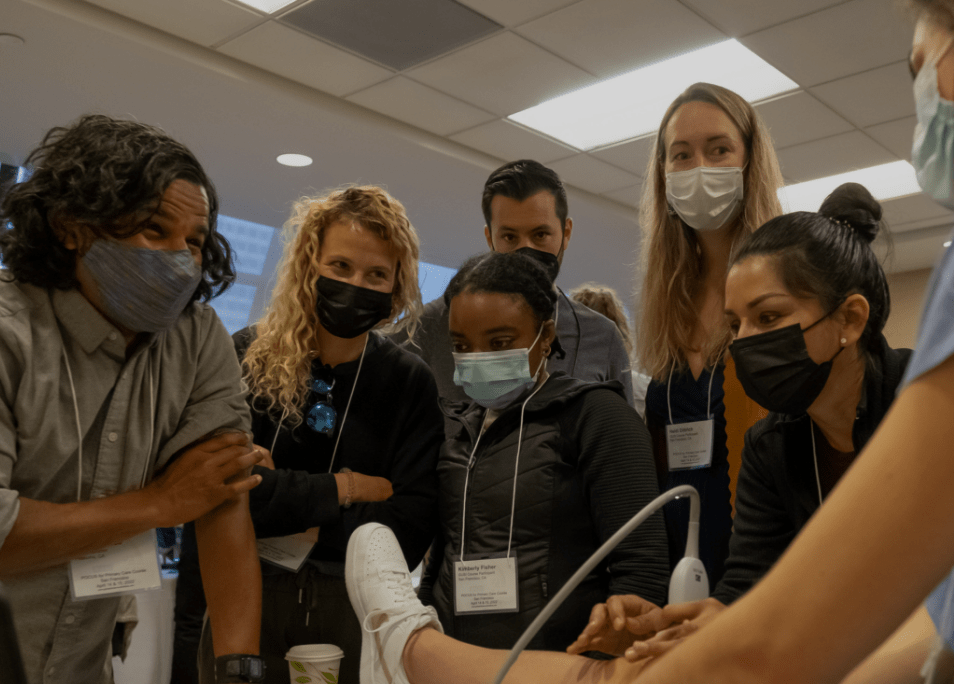

In-Person Workshops

High-yield, immersive and engaging experiences taught by doctors in practice that help you gain confidence in learning POCUS.

Online Educational Platform

Learn at your own pace with an engaging online video curriculum, Qbanks, and a built-in scan archive to save scans for credentialing.

Individual Mentorship

Elevate your clinical impact with a personalized, one-on-one POCUS fellowship designed to build confidence, expertise, and lasting mastery.

Expert-Led Scan Review

Get personalized scan feedback from expert reviewers to sharpen your skills, build confidence, and support credentialing.

Program Consulting

Boost your ultrasound revenue with tailored billing guidance, compliance support, and streamlined coding strategies from our expert consulting team.

Creating a better world with POCUS, one patient at a time.

Join us! We invite you to be a part of this expanding, global movement.

We are an inclusive, welcoming community of practitioners from many areas of clinical medicine who are passionate about Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) education, training, and patient care.

Meet the world's best POCUS Training. New classes added every month.

ONLINE LEARNING

Master Ultrasound Skills Anytime, Anywhere

Build ultrasound skills anytime with flexible, expert-led online courses designed for busy clinicians. Learn core techniques, boost diagnostic confidence, and study at your own pace with GUSI’s trusted POCUS curriculum.

LEARN MOREExplore Our Most Popular Courses

view all courses

Point-of-Care Ultrasound Essentials Course

The Point of Care Ultrasound Essentials course offers 25 CME hours and equips healthcare providers with essential ultrasound skills to improve real-time diagnostics and patient care in clinical settings.

Learn More!

Obstetric POCUS Essentials Course

The Obstetric POCUS Essentials course equips healthcare providers with the essential ultrasound skills needed to assess pregnancy and fetal health, improving patient care and diagnostic efficiency.

Learn More!

Musculoskeletal POCUS Essentials Course

Enhance your diagnostic skills with GUSI's Musculoskeletal POCUS Essentials. This self-paced course provides practical training in ultrasound evaluation of joints and soft tissues, improving patient assessment and care efficiency.

Learn More!Upcoming Events

view all eventsmeet your instructors

GUSI is a community of expert ultrasound educators and practitioners who are passionate about sharing their craft with medical professionals around the world.

view allGUSI in the world!

Join the world’s leading platform for Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) education. Empower your medical practice today!

AI in POCUS: Expert Panel Reveals the Future of Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Part 1 of a 3-Part Series on Artificial Intelligence in Point-of-Care Ultrasound Artificial intelligence in point-of-care ultrasound (AI in POCUS) is no longer a distant future. It's transforming clinical practice today. In a groundbreaking webinar hosted by Dr. Kevin Bergman and Dr. Mena Ramos, co-founders of Global Ultrasound Institute (GUSI), leading experts gathered to discuss…Read More

Building the Next Generation of Ultrasound Educators: The GUSI MedConnect Instructor Training Program

In a small practice room at Touro University California, a medical student places an ultrasound probe on a classmate's knee. He begins to guide his peer through finding the correct anatomical view. But there's a catch: he can't touch the probe, can't adjust the angle himself, can't demonstrate with his hands. For the next 15…Read More

MedConnect – Bruno Vargas

“I don’t know how to be a doctor without using POCUS.” That’s how Dr. Vargas, a physician trained in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and GUSI instructor, described his relationship with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). For the past six years, he has been working in Chiapas, Mexico, a resource-limited region where access to advanced imaging like CT,…Read More

Ready to Advance Your Medical Practice?

- Built by clinicians, for clinicians

- Backed by global POCUS training experience

- Trusted by providers across over 60+ countries

Making a Difference Around the World

18,000+

Trained healthcare professionals worldwide

10+ years

Global Outreach

100%

Focused on Improving Healthcare Outcomes with Ultrasound

Stay Ahead with the Latest in Ultrasound Education

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates on courses, events, and advancements in ultrasound training.